Disability isn’t fixed - it depends.

And it depends on more than you think.

What do Neurodivergence, Mental Health, Pregnancy and Menopause have in common? They can be, but aren’t always, disabling.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been asking the Mostly Unlearning community what conditions we consider to be a disability or disabling. The purpose wasn’t to agree, or even to define disability. It was to pause and notice what we see as a socially acceptable disability, and why. That questioning helps uncover the quiet biases and learned beliefs that might be ready for some unlearning.

In this edition, I want to explore the distinctions between disability and disabling, touch on comorbidity, and look at the contexts where these ideas matter most. I’ll break down why personal preferences are important, but without addressing social stigma we risk distancing ourselves from the very support we need.

While I have you here

This newsletter is my personal endeavour to share as I learn, and unlearn. Thank you for joining me in this unlearning journey.

One of the core tenets of Mostly Unlearning is that our systems shouldn’t rely on individual bravery, but they often do. And when they do, it’s disabled people who carry the heaviest load.

The habit of inclusion is underpinned by learning and unlearning. Mostly unlearning.

At the end of every edition, I provide unlearning prompts. These questions are designed to prompt you to reflect on your habits and consider a more inclusive approach to todays topic. It’s helped me, and I hope it helps you too.

Got a topic you want to unlearn? Send me a message or leave a comment

Poll recap

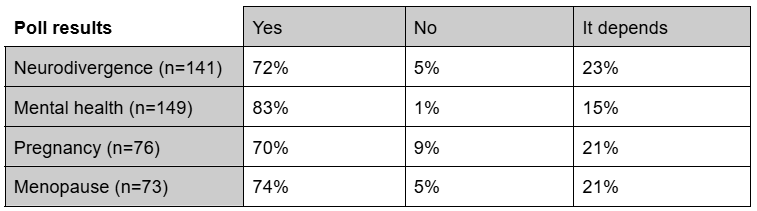

Here’s what I asked

Can neurodiversity be a disability?

Can mental health be a disability?

Can pregnancy be disabling?

Could menopause be disabling?

Across all four polls, the majority of people said yes. We were collectively most confident that mental health can be a disability (83%), most unsure about neurodivergence (23% said “it depends”) and most confident that pregnancy is not a disability (9%).

That first part surprised me. In every poll, more than 70% of respondents said “yes.” I had expected far more people to say it depends.

The truth is, it does depend.

Numbers tell part of the story, but it’s the conversation that matters. It’s in the comments where we see how people feel about disability — how we justify it, distance ourselves from it, or reclaim it. That’s where the unlearning begins.

Disability and the social model

When I ran these polls, I deliberately changed my wording from disability to disabling. It wasn’t just semantics; it was a shift in perspective.

Disability is a condition, state or identity — a noun.

Cerebral Palsy is recognised as a disability.

Disabling describes a process or action that creates a disability or something that has that effect or experience.

The policy is disabling neurodivergent people.

These office lights are disabling for people with sensory sensitivities.

Disabling happens when systems create barriers. And when those barriers are removed, the disabling effect often disappears.

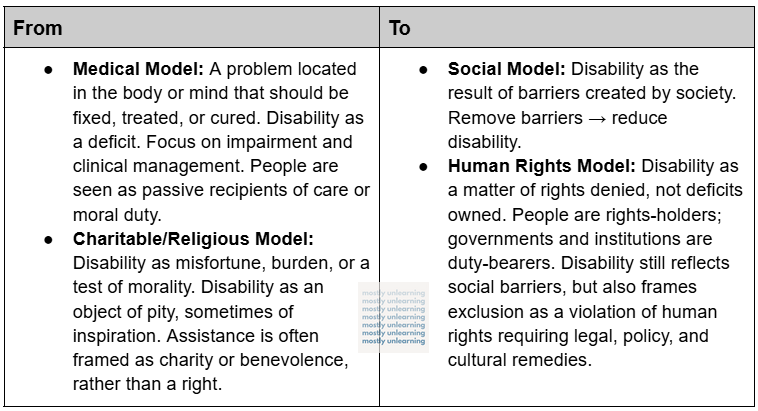

From deficit to design, disability models over time

Disability models have evolved over time, and with them, our understanding of where the disability occurs - and therefore the responsibility - lies.

This shift moves responsibility outward — from individual bodies to systems and society.

This shift has spread the load.

Instead of locating blame in the body of each disabled individual, it identifies society - our systems, organisations and designs - and their role in mismatched interactions and ability to influence. It empowers and galvanises more people to address social inequity. Because inside organisations are both people and resources, both of which can be used to build a more equal, less ableist society.

All that said, it really does depend.

It depends, on the person.

By far the most common comments were about a person’s autonomy to identify and choose, and in principle, I tend to agree.

As I’ve said before.

Disability can be subjective to the person. It undulates with circumstance and time. An individual’s relationship with disability and feelings of discrimination are theirs.

But those feelings and that relationship aren’t developed in isolation. We are all soaked in ableism, and that conditioning seeps into how we see ourselves. Even disabled people can internalise bias toward disability. We are not a monolith.

For many, resistance to using the word disability comes from the medical or charitable models, the deficit framing. I’ve felt that too. It’s the social and human rights models that soften internalised ableism; they see disability as an ordinary and expected part of human variation.

When I first acquired my disability, I had an accessible parking permit and didn’t identify as disabled. At times, I’ve known I’m disabled yet needed no support. Now, I have more support needs than ever — and I’m comfortable using the word disability.

Why does it matter if you identify with the word disability or not? The reality is that your rights are covered by laws that use the term. Experience has taught me to focus instead on knowing my rights and evolving my relationship with the terminology.

Hold lightly the word “disabled.” Hold tightly to your rights.

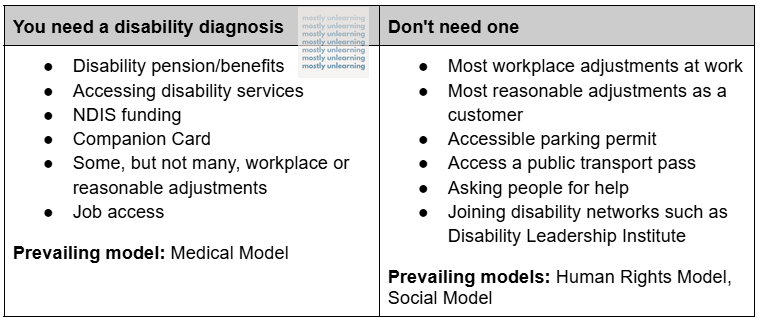

It depends, on the context / why

Context matters just as much.

Sometimes identifying as disabled is about accessing what you need — and that depends on which system you’re in.

Is it for a disability pension or benefit? For an accessible parking permit, NDIS plan, or workplace adjustment? Each asks for different kinds of proof.

Some systems, such as the NDIS, may focus on impact, but they still rely on the medical model, where evidence and diagnosis determine access. Others, such as workplace adjustments or inclusive design practices, lean more on social or human rights models — focused on barriers and rights, rather than labels.

Situation where you might need a definitive disability diagnosis. (Please confirm for your personal circumstances).

Knowing which model you’re operating within changes how you frame your needs - and how society responds to them.

It depends, on the medical condition(s)

Some disabilities are clear-cut: cerebral palsy, blindness, deafness, and schizophrenia. Others — pregnancy, menopause, neurodivergence — are more situational.

If you’ve been reading Mostly Unlearning for a while, you’ll know it was pregnancy, not my spinal injury eight years earlier, that shifted how I saw myself.

Before pregnancy, my body rarely disabled me. Pregnancy changed that — increasing pain, reducing mobility, and creating new limits. I wasn’t disabled by my impairment. I was disabled by pregnancy — a kind of comorbidity to everything else going on in my body.

Comorbidity means the presence of two or more medical conditions or disorders occurring at the same time in one person. These conditions may interact with each other, complicate diagnosis, or affect how treatment works. Many people who acquire a physical disability like mine also experience depression, anxiety, or PTSD. These are often reported as comorbid mental health conditions.

My experience of being pregnant with a physical disability is that pregnancy was disabling. Even though medically pregnancy is not a comorbidity, you get my point. That gap between lived experience and medical terminology is exactly where the social and human rights models give us better language — and more agency.

It depends, on the impact it’s having on the individual

Ultimately, the impact is what matters most. When a condition and an environment interact in ways that disable someone, then yes, that condition can be a disability.

Even the NDIS is impact-based, not diagnosis-based. It’s the intersection between body and environment that defines disability, not the body alone.

So are Neurodivergence, Mental Health, Pregnancy and Menopause disabilities or disabling?

Maybe. Sometimes. It depends.

They can be, but aren’t always, disabling.

Depending on the circumstance, condition, personal comfort or discomfort and impact.

People don’t automatically identify with the word disabled because they fit the categorisation of disabled, just as businesses don’t suddenly halt a business practice identified as discriminatory.

We are not a monolith

You don’t have to agree with me.

In having this discussion, I’m not seeking consensus; I’m seeking to open a dialogue to progress disability confidence and inclusion everywhere disabled people exist.

We are not a monolith. We don’t have to agree.

Because disability confidence and inclusion grow when we sit with complexity, not when we collapse it into a single answer.

But we are stronger together — and for that reason alone, I hope we work collectively against harmful stereotypes and towards social cohesion.

Unlearning prompts

Understanding this nuance can strengthen our individual confidence in asking for help and galvanise group movements towards broader, everyday disability inclusion.

In today’s edition, consider unlearning:

What would happen if you accepted that you are disabled?

What if mental health isn’t a “secondary condition” to spinal injury, but a signal of how deeply environments can disable?

What if disability isn’t permanent, but something that emerges when bodies and environments collide?

What if pregnancy, ageing, or injury can all be disabling — not because they’re deficits, but because society or individuals don’t adapt?

How might your relationship with the word “disabled” shift if you saw it through the social or human rights model instead of the medical model?

How might systems change if we shifted the pressure from individuals to organisations in society to design inclusively?

Join the unlearning.

My work is geared towards shifting these systems to take the pressure off people alongside commercial outcomes. You can subscribe to learn with me. I’ll share what I learn (and unlearn) about accessibility, inclusion and disability. Together, we will consider the implications for impactful commercial and human outcomes.

Other editions you might also like

In the spirit of unlearning, here are some other editions you migth enjoy.

Are you disabled? Maybe. Are you discriminating? Probably.

My full time corporate job is talking to people about disability and accessibility. There invariably comes a moment when someone says, "Wait, am I disabled too?" followed by an ‘ah-ha' moment about what discrimination can look and feel like.

Autistic Burnout

Welcome to Mostly Unlearning, a newsletter that amplifies accessibility, inclusion and disability voices towards more impactful commercial and human outcomes.

My Disability Advocacy Origin Story - Part One.

I hope this newsletter finds its way into your inbox like an old friend, one you haven't seen in forever, yet the conversation flows as if no time has passed. The last year has been a blur as I started a new job, disability ups and downs, purchasing an accessible house and leaning into supporting those around me - at work and home. As I’ve said before, …

Disability Origin Story - Part Two.

Even five years later, the memories of those early days can bring involuntary tears to my eyes. There were moments I coped well, moments I broke apart, and moments I couldn’t tell the difference.

Lived Expertise as a Profession

Welcome to Mostly Unlearning, a newsletter that amplifies accessibility and disability voices towards more impactful commercial and human outcomes.