Can neurodiversity/neurodivergence be a disability?

Welcome to Mostly Unlearning, a newsletter that amplifies accessibility, inclusion and disability voices towards more impactful commercial and human outcomes.

A recap for the newbies

Whether you’re here as a colleague, designer, leader, policy maker, or disability advocate, thank you for unlearning with me. One of the core tenets of Mostly Unlearning is that our systems shouldn't rely on individual bravery, but they often do. And when they do, it's disabled people who carry the heaviest load.

The habit of inclusion is underpinned by learning and unlearning. Mostly unlearning.

At the end of every edition, I provide unlearning prompts. These questions are designed to prompt you to reflect on your habits and consider a more inclusive approach to the edition's topic. It's helped me, and I hope it helps you too.

Back to this week's edition - can neurodiversity/neurodivergence be a disability?

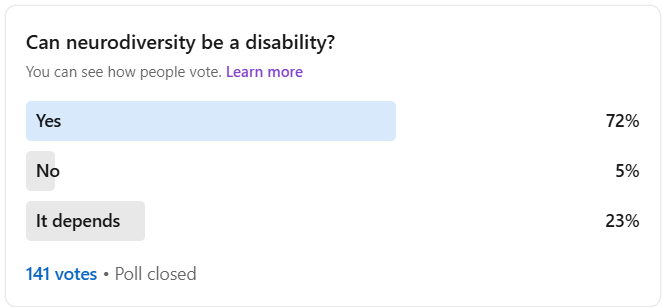

Last week, I asked my LinkedIn followers if neurodiversity could be a disability. I initially shared this poll as a teaser to last weeks Mostly Unlearning edition, but the conversation sparked a full edition of thoughts.

In today's edition, I continue to explore why neurodiversity is sometimes disabling — and why recognising this matters. Or as

saidWhat is a disability?

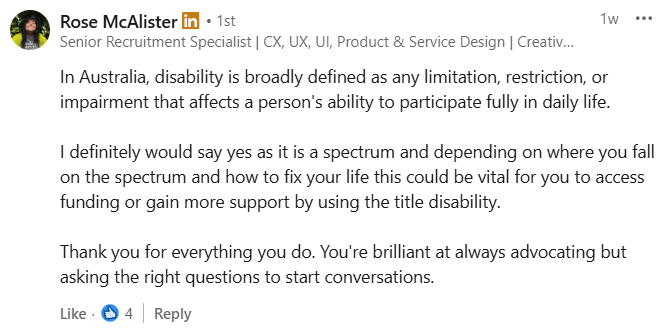

Let’s start there. Rose McAlister commented, "In Australia, disability is broadly defined as any limitation, restriction, or impairment that affects a person's ability to participate fully in daily life." This aligns with the broad definition in the Disability Discrimination Act.

The Australian Human Rights Commission explains, “It includes physical, intellectual, psychiatric, sensory, neurological and learning disabilities. The Act covers disabilities that people have now, had in the past, may have in the future or which they are believed to have.”

Vague. Broad. Contextual.

Disability can be subjective to the person. It undulates with circumstance and time. An individual's relationship with disability and feelings of discrimination are theirs. As my co-lead for colleague engagement, Dana Thompson, expressed in her response to this poll.

Neurodiversity and neurodivergence.

As

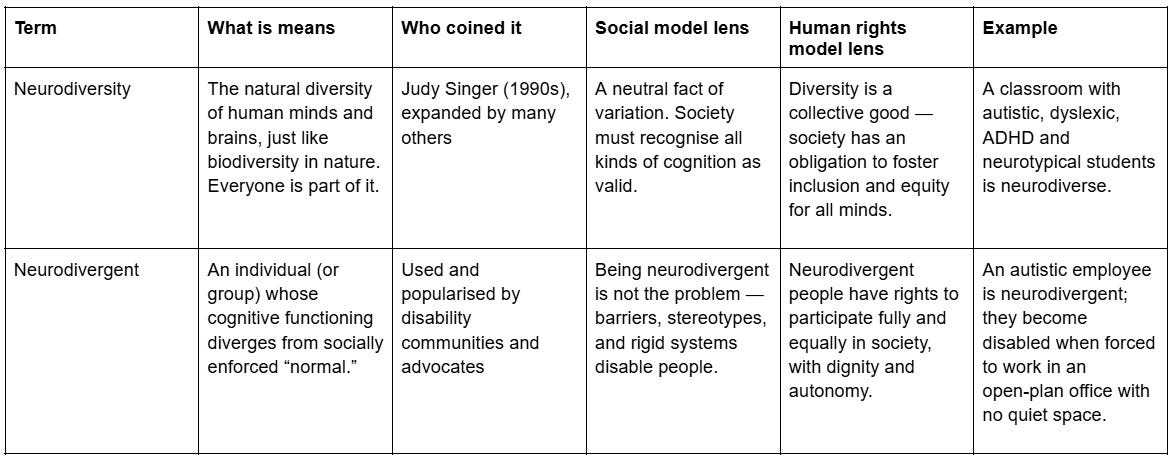

rightly pointed out, neurodiversity and neurodivergence aren’t the same thing. I should have used the term neurodivergent in the question wording.In researching this edition, I learnt there are many ways to define neurodiversity and neurodivergence. What is consistent is that one is universal and the other is individual. In the tables below, I summarise how I've come to understand both terms within the social and human rights models.

So why refer to it as a disability?

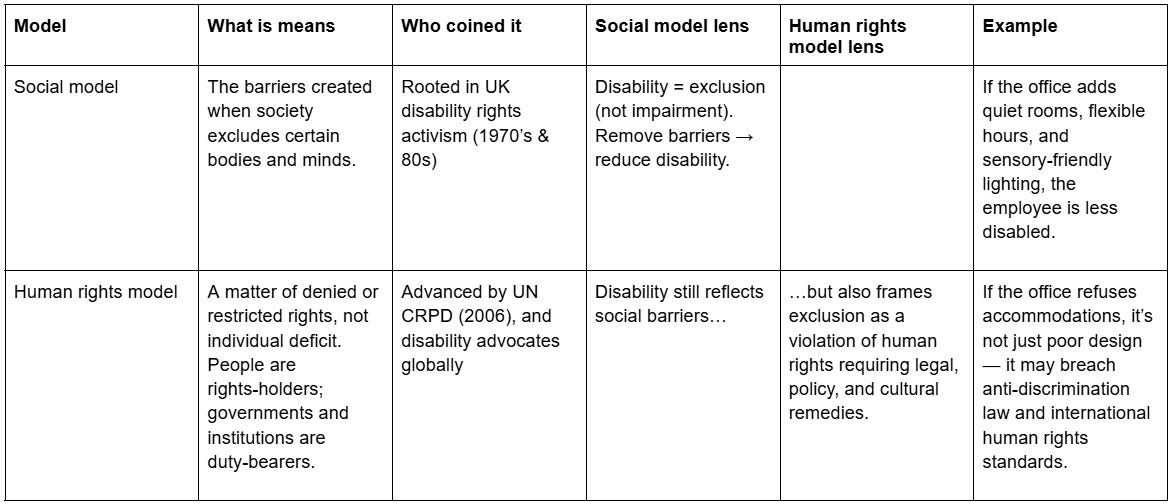

Whether you use the social or human rights model of disability, all of this is normal, expected human variation. For many, resistance comes from medical or charitable models’ framing of deficit — I’ve felt that too. It’s the social or human rights model that softens internalised ableism as a driver.

So why refer to it as a disability? Three reasons

One, under the social model of disability, society has disabled some neurodivergent people, their expressions and traits.

Two, because they are covered under disability legislation, and I think it's important for people to know their rights.

I’ve come to realise it is essential to know your rights and that the law happens to have the term disability in it. The law protects your rights under the word disability — even if you don’t identify with the word yourself.

So, are you disabled?

Maybe. Why does it matter if you identify with the word disability or not? The reality is that your rights are covered by laws that use the term. But people don't automatically identify with the word disabled because they fit the categorisation of disabled, just as businesses don't suddenly halt a business practice identified as discriminatory.

Experience has taught me to focus instead on knowing my rights and evolving my relationship with the terminology. A point I expand on in "Are you disabled? Maybe. Are you discriminating? Probably."

Hold lightly the word disabled. Hold tightly to your rights.

Brooke Szücs No, but it’s probably influenced people’s responses.

A side quest on the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and Neurodiversity, specifically Autism

Autism is the most common primary diagnosis on the NDIS, and children with Autism are the fastest-growing participant group in the NDIS. ChatGPT tells me Autism makes up ~35% of total participants and ~20-25% of total budget on the National Disability Insurance Scheme. ADHD, on the other hand, is not considered a primary diagnosis and, on its own, would not get you access to the NDIS. To me, at least, this says some types of neurodivergence are considered a disability by the Australian Government.

Side, side quest

When announcing the new Thriving Kids program, the NDIS Minister’s words, referring to ‘mild and moderate autism,’ echoed deficit language that many in the disability community have long challenged.

Barriers exist, and they are disabling.

I love this comment from Lauren Hoey “Neurodiversity reminds us that many of the challenges neurodivergent people face aren’t inherent to their brains, but are shaped by living in a world largely designed for neurotypical norms. The impairment may be real—such as difficulties with reading, focus, or sensory processing—but disability is created when environments fail to adapt.”

You don't have to agree with me.

In having this discussion, I’m not seeking consensus; I’m seeking to open a dialogue to progress disability confidence and inclusion everywhere disabled people exist. We are not a monolith, and we do not have to agree.

The third reason I refer to neurodiversity and neurodivergence as a disability? We are stronger together. For that reason, I hope we can work together against harmful stereotypes and towards social cohesion.

Disability is not a dirty word. Neurodivergent people can be disabled.

Unlearning prompts

Identity & Language

What if avoiding the word “disability” limits access to protections meant for you?

How might your relationship with the word “disabled” shift if you saw it through the social or human rights model instead of the medical model?

Rights & Disclosure

What if disclosure wasn’t about proving worthiness, but about unlocking rights already yours?

How might workplaces look different if design assumed non-disclosure as the norm, rather than disclosure as a requirement?

Business & Design Responsibility

What if every inaccessible process or product was understood as a form of discrimination?

How might commercial outcomes improve if businesses treated accessibility as a baseline, not an add-on?

Power & Perspective

What if unlearning ableist assumptions freed you to see neurodivergence as talent, not a deficit?

How might systems change if we shifted the pressure off individuals and onto organisations to design inclusively?

Join the unlearning.

My work is geared towards shifting these systems to take the pressure off people alongside commercial outcomes. You can subscribe to learn with me. I'll share what I learn (and unlearn) about accessibility, inclusion and disability. Together, we will consider the implications for more impactful commercial and human outcomes.

Excellent piece!